Docker Machine

Docker machine is a component of Docker that can be used to switch between Dockerized hosts, including those on remote services such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Digital Ocean. Docker Machine is now installed as a part of the overall Docker install, so if you have not yet installed Docker, or if you are unfamiliar with Docker, you should first go through the Docker tutorial.

A deeper understanding of how Docker works

In order to work with Docker Machine without getting confused, you need to have an understanding of some details of how the Docker system works.

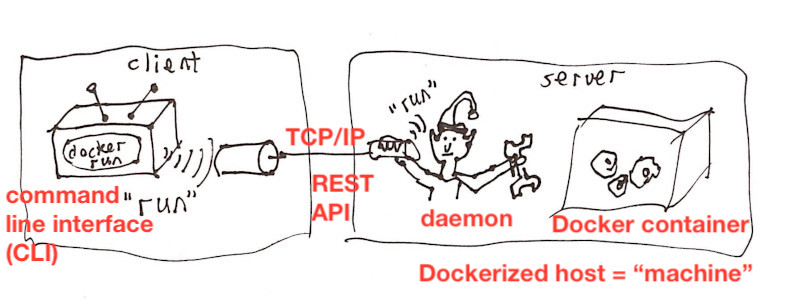

On the largest scale, the Docker system involves communication between a client (software on your local computer) and a server (a separate software system that might be on your local computer or on a remote computer somewhere else). Communication between the client and the server takes place using the Internet protocol called TCP/IP.

On the local computer, the software is run through the Docker command line interface (CLI) – software that you invoke by typing commands in the console (Terminal on Mac or Command Prompt on Windows).

In the Docker system, the server is known as a “Dockerized host”, colloquially referred to as a machine. The machine has several components. An important one is the daemon, a system in the machine that manages the docker containers that exist on that machine. The daemon does things like downloading Docker images, running new containers, and starting and stopping existing containers. The containers themselves are part of the machine, and when they are started, they are what actually make the machine “run”. Communication between the daemon and the CLI takes place through the machine’s REST API, a system that is able to send and receive TCP/IP commands from the CLI.

When you are running generic Docker out of the box, you are actually using a machine that is operating on your local computer. In this case, the TCP/IP commands don’t actually go through the Internet, they simply loop back from the CLI to the local machine using the localhost address – a special IP address that allows communication to a server within your computer. If the only machine you are running is the default local one, you don’t really need to be aware of all of the details. But if you are running multiple machines, you need to understand the pieces and how they communicate with each other.

How does Docker Machine work?

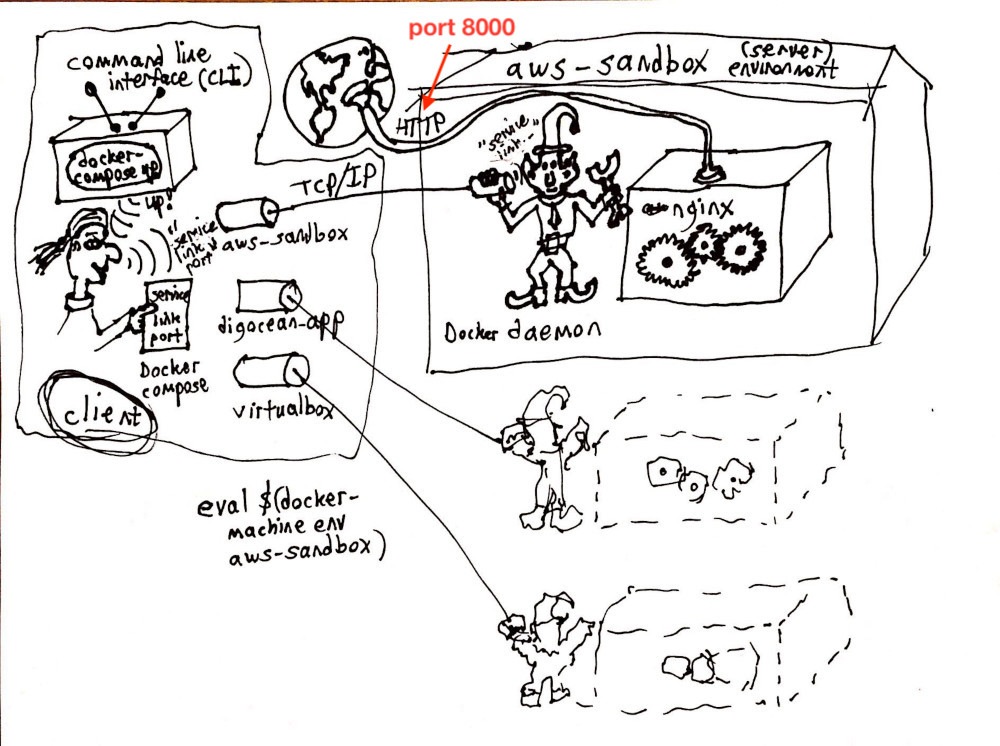

The diagram below shows an over-simplified diagram of how Docker Machine works.

The primary difference between this diagram and the previous one is that there are now several machines that Docker can communicate with. Docker Machine manages the creation and destruction of these machines, and can list them and describe their properties. It also controls which of the machines the Docker CLI is talking to at any particular moment (it can only talk to one at a time).

The other complication that is introduced in this diagram is the presence of Docker Compose. Docker Compose is an intermediary that can coordinate the activity of multiple Docker containers. The “script” that orchestrates this activity is a YAML file that is typically called docker-compose.yml. If a generic docker command such as

docker restart webserver

is issued from the CLI, it goes straight to the daemon, which carries out the command directly (as shown in the previous diagram). On the other hand, if a docker-compose command such as

docker-compose up

is issued through the CLI, the Docker Compose system carries out the tasks described in the YAML file by issuing multiple commands to the daemon.

Examining and switching Docker machines

If I want to see what machines my system can access, I can issue the command

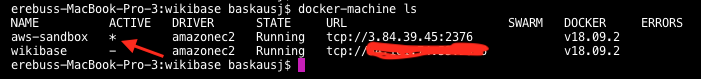

docker-machine ls

The list will show all of the machines that I have created using Docker Machine. (There is also the localhost machine, which exists, but is not shown in the list.)

Notice that there is a star in the ACTIVE column for the aws-sandbox machine. This means that the aws-sandbox is the machine that Docker will be taking to when you issue Docker commands. It does NOT mean that the machine instance is running (that’s indicated in the STATE colunm), nor does it mean that any particular container has been started. If no listed machine has a star in the ACTIVE column, then Docker commands that are issued will go to the localhost machine. (In the diagram above, the star indicates which of the “string telephones” we are communicating through.)

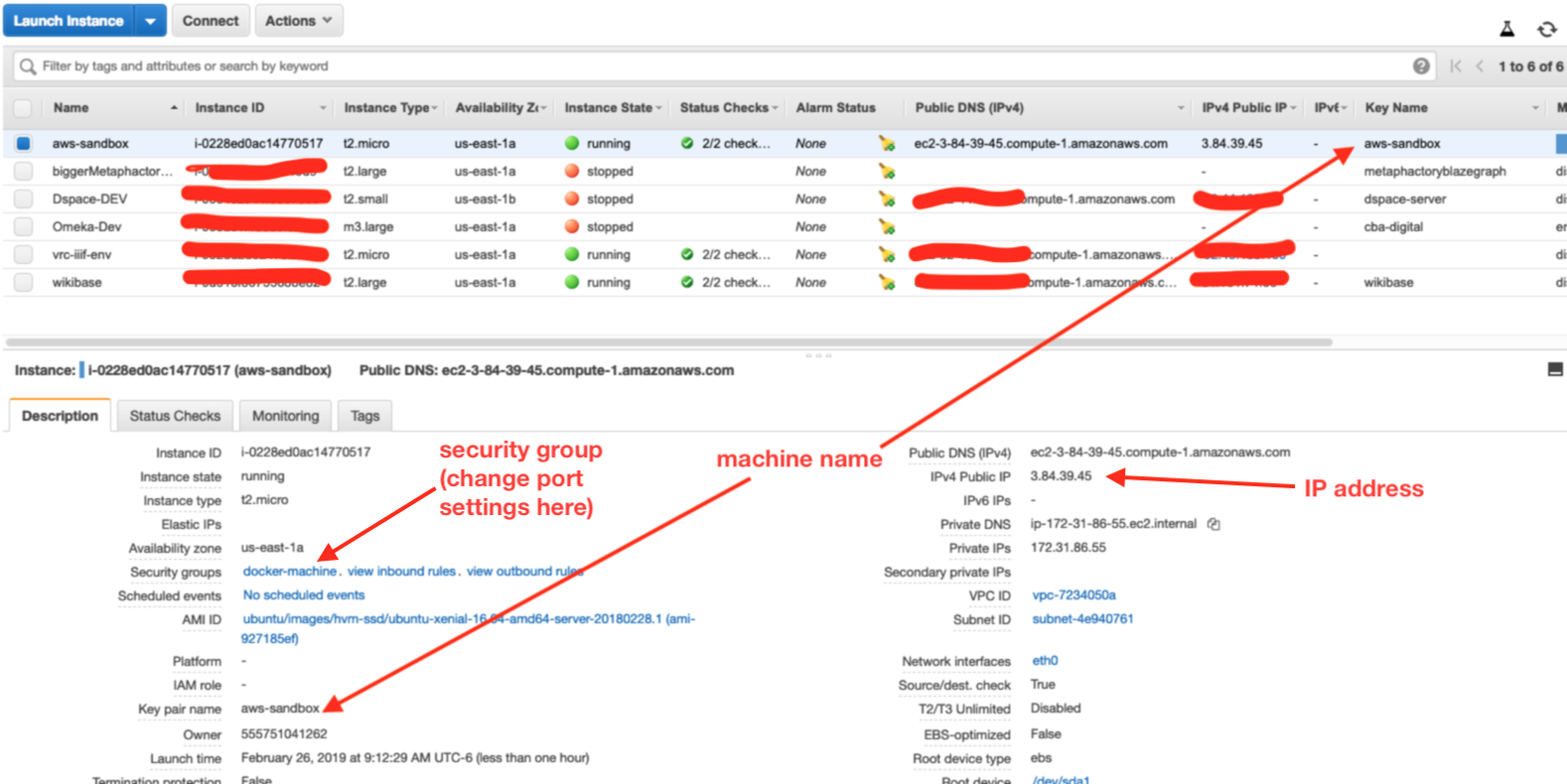

In this case, the aws-sandbox machine is running on Amazon Web Services (AWS) Elastic Computing (EC2) platform. If I look at my AWS EC2 console, I can see both of the Docker machines that I started up from my local computer. I can also see several other EC2 instances that were not set up using Docker.

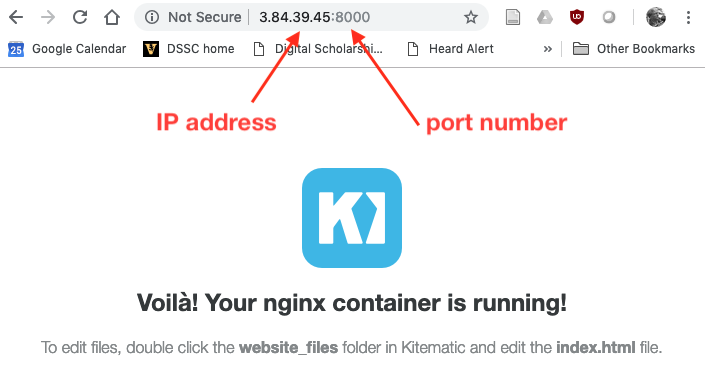

Docker machines generally operate as servers that communicate through IP addresses (through the Internet unless it’s the localhost). When Docker Machine creates a machine on some service like AWS EC2, it acquires an IP address that is often assigned dynamically by the service. That IP address is shown both in the Docker Machine CLI listing and also on the AWS EC2 console. In this example, the IP address is 3.84.39.45. This is the IP address that would need to be put into a browser bar to interact with the server. Additionally, there is a particular port number that the server uses to talk to the outside world. This example is from the Docker machine AWS EC2 examples page, which sets up a test server named “webserver” that communicates through port 8000:

docker run -d -p 8000:80 --name webserver kitematic/hello-world-nginx

If I enter the IP address and port 3.84.39.45:8000 into a browser bar, I see the sample web page that was produced by the nginx webserver container running in the machine aws-sandbox.

Note that getting a web page from the nginx webserver requires that the kitematic/hello-world-nginx container (named “webserver”) must actually be running. It is not enough for the aws-sandbox machine to exist and be running (although that is also a necessary condition). Once the webserver is running, it is irrelevant whether aws-sandbox is the active Docker compose machine or not. The machine will continue in its current state, with containers running or not, regardless of whether it’s connected to the Docker machine CLI on my local computer (i.e. the active machine).

To change the active machine using the Mac or Linux terminal, you can use the command:

eval $(docker-machine env aws-sandbox)

where you replace asw-sandbox with the machine you want to make active. (At this time, I don’t know the equivalent command for Windows Command Prompt. This eval command is platform-dependent, unlike actual docker-machine, docker, and docker-compose commands.) To deactivate all active machines and reconnect Docker to the localhost machine, issue the unset command:

eval $(docker-machine env -u)

Security Certificate Issues

There are two critical issues involving security certificates that you need to understand before using Docker Machine.

Switching local computers

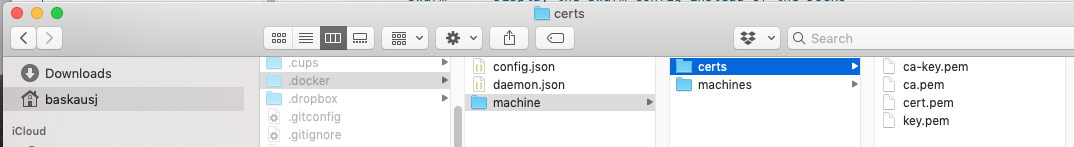

When Docker Machine communicates with a service to set up a new machine, it communicates with the service about two sets of security certificates. On set is the certificates for the Docker Machine instance itself. These certificates are in a hidden directory in the user directory. The subdirectory path is .docker/machine/certs/. These are the certificates that are needed in order for the service to know that it’s communicating with the correct computer.

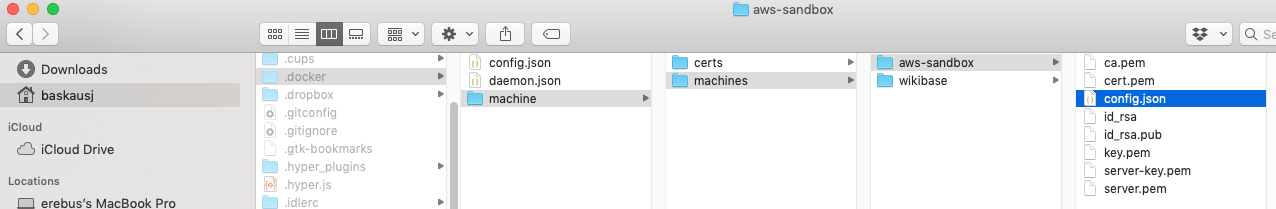

The other set of certificates are machine-specific. They are located in a directory named after the machine, nested within a machines directory, for example .docker/machine/machines/aws-sandbox/.

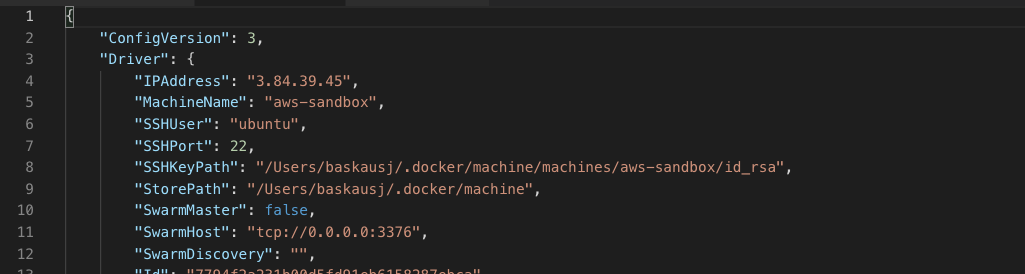

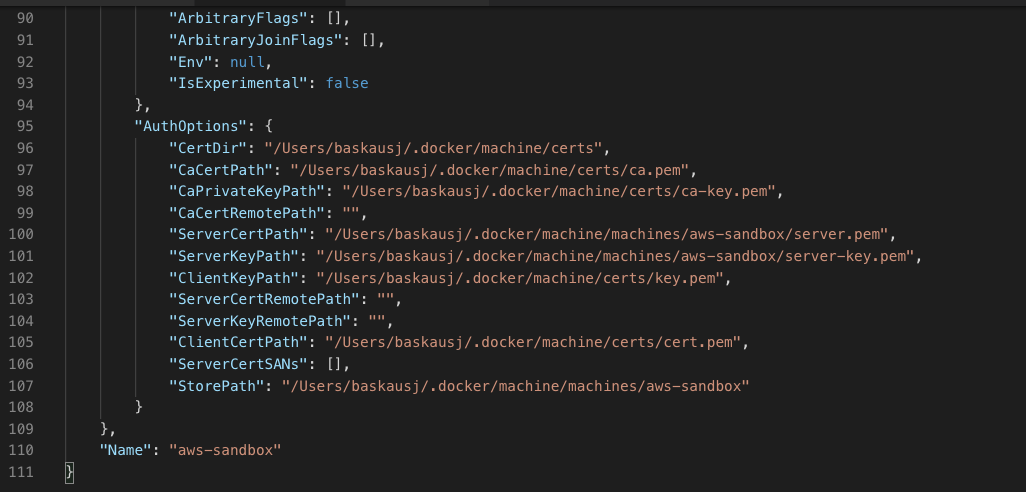

When Docker Machine wants to know what machines it can control, it looks at the config.json files within each of the machine directories. The config.json file tells Docker Machine where the various certificates that it needs can be found by means of absolute file paths. Here’s what part of a config.json file looks like:

...

If a particular computer does not have the certificates for the machine and for the Docker Machine instance that created the machine, it is not possible to communicate with the machine using the CLI. Of course you could shut down or destroy the server instances using a different interface such as the AWS console, but you could not control the containers within them because you would be unable to establish secure communications with the daemon inside the machine.

There is a somewhat complicated solution to this problem. You need to move the machine’s directory into the machines directory of the other computer that you want to use to control the machine via Docker Machine. You also need to move the Docker Machine security certificates (that were located in the certs directory of the original computer). However, you can’t just replace the ones in the target computer’s certs directory, because that would make it impossible for the target computer to communicate with any existing machines it had created. So you need to create a different directory in the target computer to contain the certificates from the original computer.

The final step is to edit the config.json file for the machine whose certificates were moved so that the absolute paths in the file reflect the absolute paths of the file locations on the target computer. Once this is done, the Docker Machine on the target computer will be able to “talk” to the machine that was created on the original computer.

Understanding this is critical if you are working on a real project because if you don’t have a copy of the Docker Machine and machine certificates somewhere and the hard drive crashes (is stolen, run over by a train, etc.) you will have no way to communicate with the daemon in the machine to make changes.

Although I haven’t tried it, it is probably also possible to just use the same Docker Machine certificates on different computers from the start (rather than letting Docker Machine generate them the first time it creates a machine). Then one could just point the URLs in the moved machine directory to the existing Docker Machine certificates rather than having to move them as well.

Stopping the server instance

The other serious issue is related to the changing of IP addresses when the machine is stopped and restarted. This issue arises regardless of whether the machine is stopped and restarted using Docker Machine itself, or if it is stopped and restarted using something like the AWS EC2 console.

Unless the machine has a fixed IP address, when the machine is stopped the dynamically assigned IP address is lost. When the machine is restarted, the service (e.g. AWS) assigns the machine a new IP address. However, the IP address is embedded in the security certificates, so if it changes, the certificates become invalid. It is possible to re-issue new certificates, but since you can’t communicate with the machine except by using the now-invalid certificates, there is no way to “talk to” the daemon and let it know to use a new certificate for the new IP address.

There is undoubtedly some work-around for this, but as of this writing, I don’t know what it is. So without further information, it is critical that you leave the machine running until you no longer need to use it.

Commands cheat sheet

Create a new Docker machine (hacked from here):

docker-machine create --driver amazonec2 --amazonec2-open-port 8000 --amazonec2-region us-east-1 --amazonec2-instance-type t2.large machine-name

Note the instance type option that isn’t give in the original example (default is t2.micro).

List Docker machines:

docker-machine ls

Look for the * that indicates which machine is active (connected to Docker).

Change active machine:

eval $(docker-machine env machine-name)

Unset machine (activate localhost machine):

eval $(docker-machine env -u)

Display the contents of the active machine’s config.json file:

docker-machine inspect machine-name

Go to the Linux terminal prompt INSIDE the machine:

docker-machine ssh machine-name

(Enter exit to return to the prompt of your local computer).

Terminate the machine:

docker-machine rm machine-name

Note: this removes the machine, including all of the containers and images within it. This is the nuclear option. On AWS, the status of the machine instance state changes to terminated and eventually it disappears from the list.

What’s next?

Clearly there is a lot more to know about using Docker and Docker Machine. This is only intended to be a conceptual overview. You should check out the Docker Machine documentation for the details and commands necessary to create and manage machines.

Revised 2019-02-26

Questions? Contact us

License: CC BY 4.0.

Credit: "Vanderbilt Libraries Digital Lab - www.library.vanderbilt.edu"