Ways to use Git and GitHub

If you have heard of GitHub, you probably are wondering “what is it for?” and “how do I use it?”. Those are complicated questions, because there isn’t just one use for GitHub and there are many ways to interact with it. In this lesson, we’ll talk about several ways that people use GitHub without delving into any of the gory details.

To clarify some terminology, Git is a version control system (often executed using command line instructions) and GitHub is a web service that allows users to store files remotely using Git. You can interact with GitHub using command line Git, through a graphical interface called the GitHub desktop client, or through a web browser using the GitHub website.

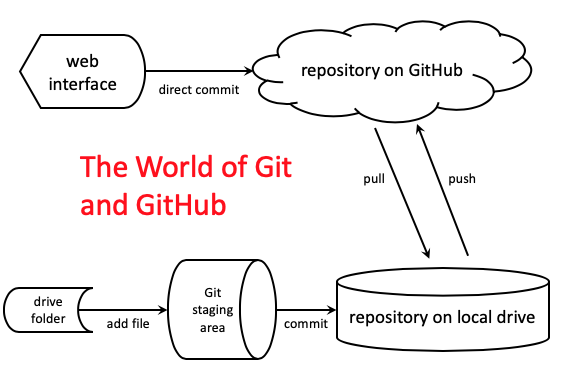

The World of Git and GitHub

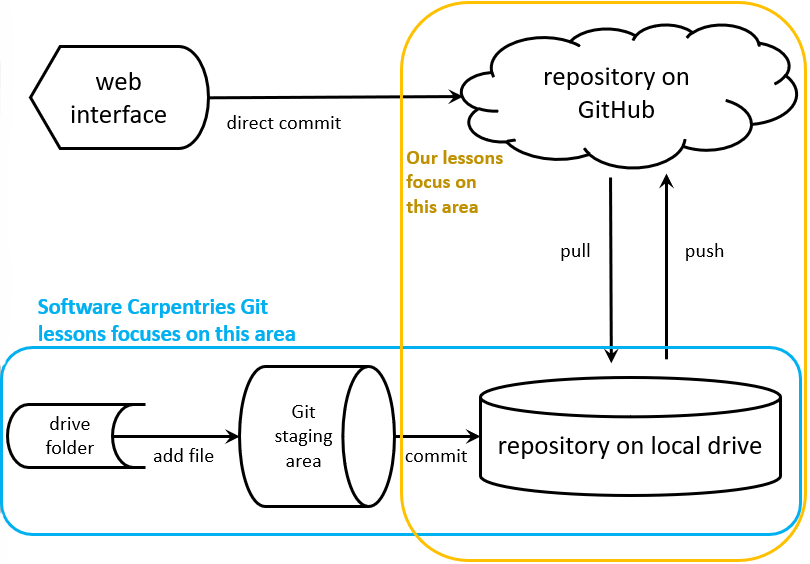

The following diagram shows the most important pieces of the GitHub universe. There are many more details that we’ll examine later, but these are the main components.

The bottom half of the diagram shows parts of the universe that live on your local computer (laptop or desktop). The top half of the diagram represents the GitHub web service.

The parts on the bottom half aren’t really different physical things since they all live on your hard drive. Rather, they are conceptual parts of the system. It’s possible to use only this bottom half of the diagram (on your local computer) and never interact with the top, remote half (GitHub). There are people who use command line Git solely to manage versions of documents on their local computer and never actually move files to or from GitHub.

Here’s how you can think about the pieces on the lower half. The local drive repository is a place where files have been put for permanent storage under version control. That means that every historical version of a file is tracked and it’s possible to look at or recover any older version back to the creation of the repository. The drive folder is just a regular directory in your file system. Files can live there, but Git will not necessarily be paying attention to what’s going on with them. The staging area is a place where Git is paying attention to files it contains, but those files have not yet been committed to the version control system.

The repository on GitHub and the local repository are copies of each other. In that sense, they are like Dropbox, Box, OneDrive, or other cloud storage services. However, the transfer of files to and from GitHub from the local repository is not automatic. Rather, individual files move from the local repo (slang for “repository”) to GitHub when they are pushed, and files move from GitHub to the local repo when they are pulled.

Having a local repository mirrored on GitHub is a safeguard for the files. You can delete the entire local repository and easliy just download the whole thing again on the same computer or a different one. The process of downloading the entire repository from GitHub to your local computer is called cloning the repository.

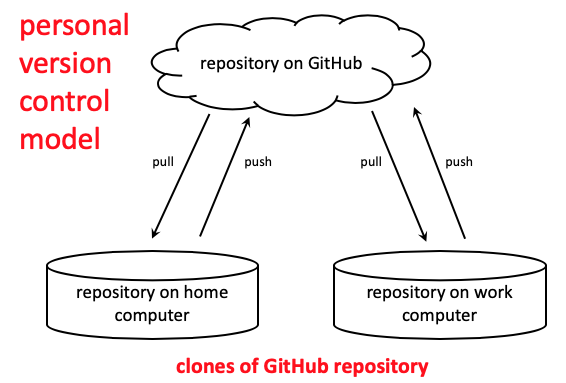

Personal version control model

Cloning a GitHub repository, then managing your personal files on one or more local computers using Git forms the basis of a simple system of version control that will safeguard your files from accidental loss, including both hard drive crashes or accidental deletion.

The diagram above shows repos on two separate local computers interacting with the same online GitHub repository. Unlike other cloud storage services, the movement of files back and forth from the cloud to the local computer doesn’t happen automatically. So files changed on the work computer won’t appear on the home computer unless they are pushed to GitHub before leaving work and pulled to the home computer after getting home from work. That could be a bad thing if you forget to do the push at the end of a work session, but could also be a good thing if you completely mess up a project on one of the computers. With a normal cloud service, messing up a project on one computer would simultaneously mess up the project everywhere else, but with GitHub you could just delete the compromised local repo and reclone it from GitHub on the cloud.

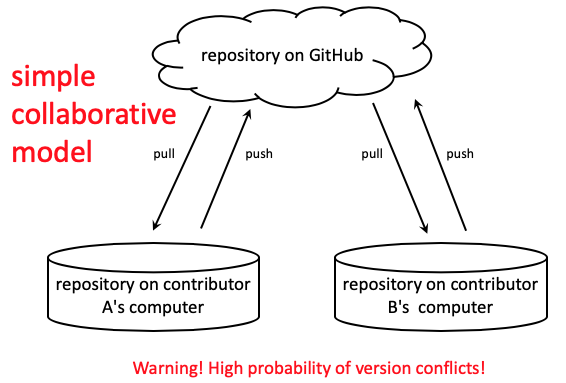

A simple collaborative model

The personal model can easily be expanded to a collaborative model where two or more people interact with the same repo on GitHub.

In this model two people share a repository and each person pulls and pushes common files from the repository as they carry out work. This works out quite well if both people never work on the same file at the same time, but if both collaborators edit the same file and try to push it to GitHub, a version conflict may arrise. This is a very different situation from Google Docs where a change made by one collaborator appears simultaneously in a document with changes made by another collaborator.

Fortunately, there are ways to resolve these kinds of version conflicts, but if its likely that two people will be working on the same files, there is a better system.

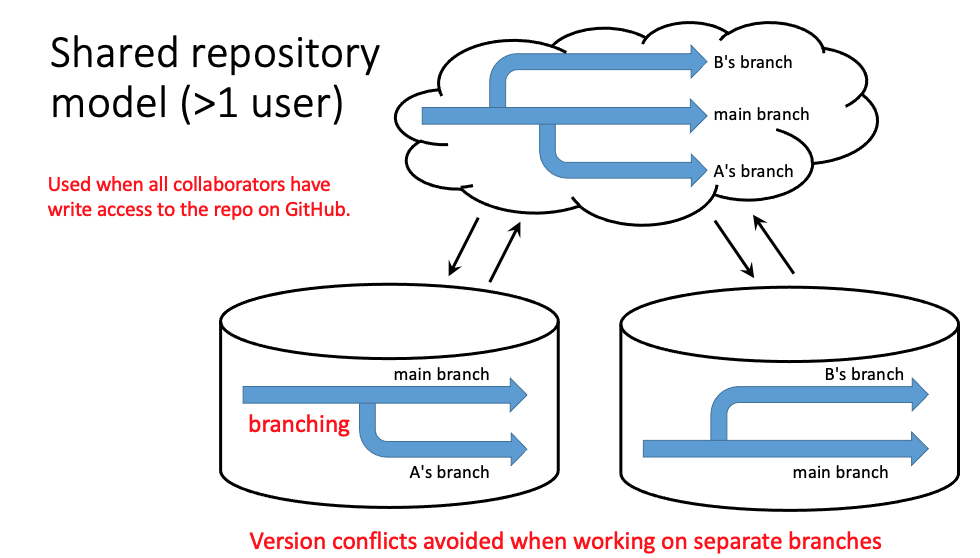

The Shared Repository model

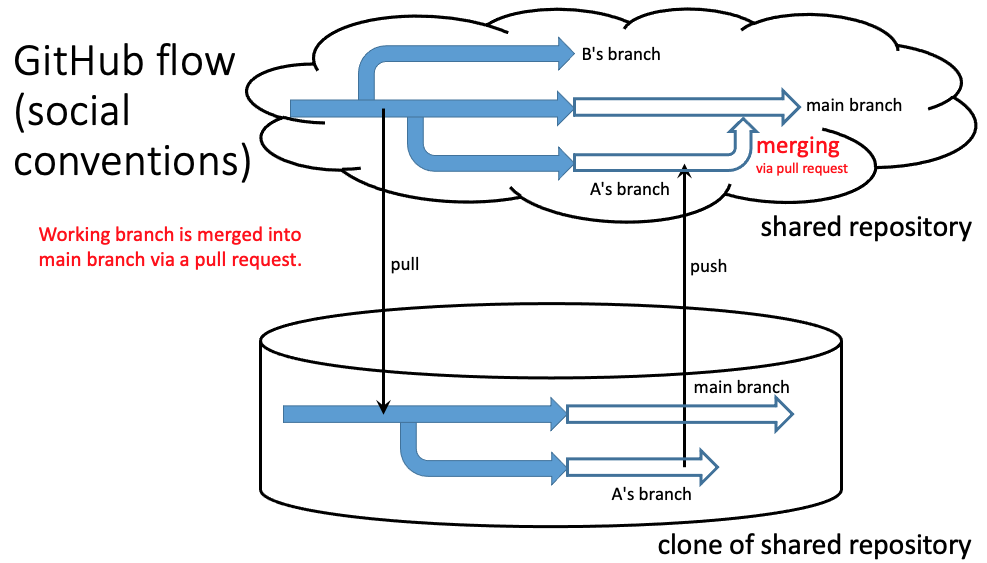

The following diagram shows a variation on the simple collaborative model above.

As before, both collaborators share access to a common repository and both can push and pull files from GitHub any time they want. However, in this model, before making changes to the master branch (the master copy of the project), collaborators create their own working branches. The working branches start off as identical copies of the master branch, but over time they accumulate differences. However, since each branch is separate, pushing your personal branch to GitHub will never cause a version conflict since GitHub keeps a separate record of each branch.

If each collaborator works on a separate branch, how do their changes ever get incorporated into the master branch? When the team is ready to accept a collaborator’s work into the master branch, someone performs a merge of the working branch into the master. Before carrying out the merge, one of the collaborators creates a pull request. A pull request is NOT a request to immediately merge, but rather indicates the beginning of a review and dialog about the proposed changes. A significant amount of time can elapse between a pull request and a merge, and additional changes may be required on the working branch before its changes are actually ready to be incorporated into the master. (Note: “pull” in the context of pull requests means to pull changes from a branch into the master. That’s a different process from “pulling” changes from GitHub to a cloned local repository.)

The Open Source (or “fork and pull”) model

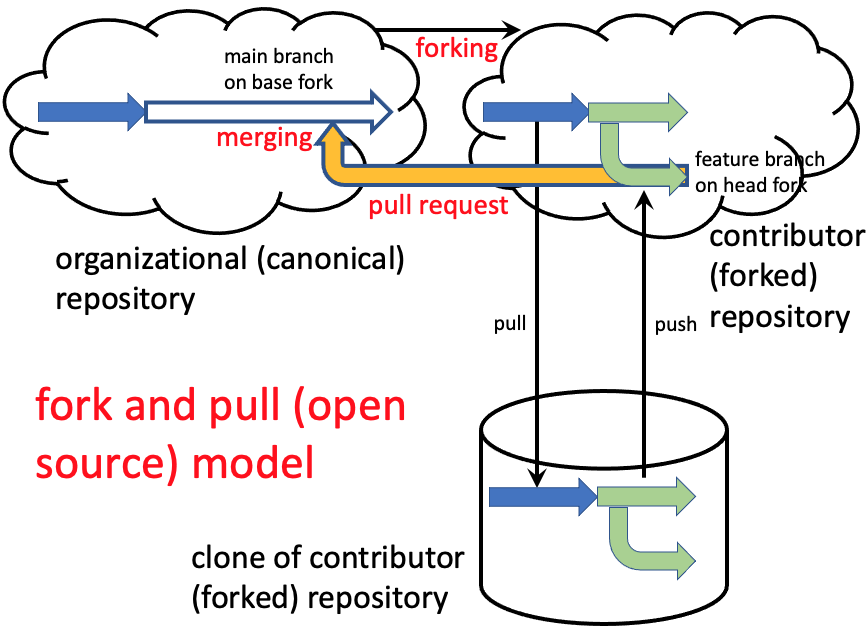

The Shared Repository model works well for small teams that are in close communication. However, in large organizations, it may be unwise to grant push access for the organization repo to all team members. In the case of open source projects, it may not even be possible to know who all of the potential collaborators may be on the project, since any member of the public can contribute.

To deal with this situation, a more complicated model is needed. The diagram above is pretty complicated, so we won’t worry about the details yet. However, the main point is that potential contributors begin work by making their own copy of the entire organizational repository on their own personal GitHub accounts (as opposed to creating a fork directly in the organization’s repo). A complete copy of a repo in a different account is called a fork and making such a copy is called forking a repository. The interactions that the contributor has with his or her fork are completely independent from what is going on in the organizational repository. Sometimes people will fork a repository just to play around with it and then destroy the whole fork when they are finished. But if the potential contributor has created some new feature that he or she thinks would be beneficial to the organization, it’s possible to make a pull request to pull a branch from the contributor’s fork into the master in the organization’s repo. If the request is merged, the creator of the changes becomes an official contributor to the organization’s project.

Other uses of GitHub

There are at least two other uses of GitHub. One is to use the free website-building capabilities of GitHub called GitHub Pages. In that case, changes made to Markdown or HTML documents move primarily in the direction from the local computer to GitHub, although it’s possible to make edits to the documents directly using the GitHub web interface.

Another important use of GitHub is its collaborative tools such as its issues tracker, milestones, and project boards. These features allow users to track progress on a project in a manner similar to the commercial product Trello. Typically, the GitHub tools are used in conjunction with managing documents by one of the collaborative models described above. However, the collaborative tools can also be used alone without any pushing or pulling of documents from a local computer.

Command line Git

Note: This is a technical topic. You can skip it if you aren’t interested and will have no problems in subsequent lessons. In future lessons, some sections of text will be marked Command line comparison. These sections will only be of interest to technical users and may also be safely skipped if you only want the general introduction.

You may already have experience using command line Git or be interested in learning it. If so, you may be wondering how command line Git relates to the GitHub desktop client that we will be using exclusively in these lessons.

Both command line Git and the GitHub desktop client use a special hidden directory called .git to manage the repository housed in a particular directory in the local filesystem. (If you have changed your system settings to make hidden directories visible, you can see this directory in each folder that is being managed by Git – but don’t edit or delete any of the files in it!) Since both the desktop client and the command line use the same protocol and files to track changes, in theory you could go back and forth between them when managing a particular repository. However, experimentation has shown some differences between the two systems in treatment of files added for staging. So it’s probably better to stick with one system or the other, at least during a particular editing session.

Command line Git has many features and options that aren’t present in the desktop client. Command line Git is also the only way to correct some complicated problems that can arise. So advanced users will probably eventually need to learn to use Git from the command line.

The Software Carpentries lesson on Git is a good place to start learning about command line Git. However, be aware that its lessons are very focused on examining and controlling what is going on within the repository on a single user’s local drive, while these lessons are much more concerned with the interactions between the local repositories of multiple users and GitHub in the cloud. In our lessons, we will start by creating a repository on GitHub, then cloning it to your local drive. In the Carpentries lessons, they begin by creating and working with a repository on the local drive and only get into interacting with GitHub after six lessons.

next page: Introduction to GitHub

Revised 2019-10-07

Questions? Contact us

License: CC BY 4.0.

Credit: "Vanderbilt Libraries Digital Lab - www.library.vanderbilt.edu"